For something so common and inconspicuous, sugar (sucrose) has managed to permeate much of our world. It has “…helped create the system of political institutions, economic forces, and cultural constraints that govern us to this day (

Charles 2002: 132)”. From its birth in southern China as

Saccharum sinense, the sugar cane was cultivated as

S. officinarum (

Dalby 2000: 26) and thus, its journey began. But sugar today cannot be used in the context of just sugar cane, instead sugar is found as an “indirect-use product (

Mintz 2008: 99)” located in manufactured products, both sweet and unsweet (

Mintz 1985: 195), such as Coca-cola and jam. This essay looks at sugar’s bad reputation; addiction and overconsumption through taste and slavery, of a product that has influenced so many of our lives today.

The taste for sugar is universal to humans, a genetic predisposition to the sweet. Newborns are found to prefer sugar solutions over water or less sugary solutions (

Birch 1999: 46), with “Neonates prior to any feeding experience…” exhibiting “…distinct facial responses to sweet and bitter substances: a marked relaxation of the face versus open-mouthed grimacing with a flat, protruded tongue.” (

Harris 1987: 80), and, if sweet substances are introduced into the amniotic fluid, the foetus begins to suckle (

De Snoo 1937, cited in Armelagos 1987: 580). The preference for sugar may be due to ecological reasons whereby sweet-tasting foods indicate high-energy substances and a predictor of nutritive value, while bitter substances may indicate poisons produced by plants (

Harbottle 1997: 182, Harris 1987: 80). This is similar to other frugivorous primates, whereby the motivation for fruit seeking may partly be due to the high palatability for sugars (

Simmen 1997: 31), where primates in the Amazon forest have a higher threshold for sugar than those living in open dry forests (

Hladik 1997: 23), like that of human populations living outside of the African forest, having higher sensitivity to sucrose than those living in the forest (

Ibid: 22). This is due to the African rain forest having fruits rich in sugar compared with outside the forest, where fruits are limited, with low sugar content (

Ibid: 23), hence lower levels of taste perception for sugar, results in an increased motivation for it.

Certain academics disagree that the predisposition for sweet substances is genetically encoded, such as Lupton (

1996: 7), who says that the “…experience of eating is intertwined with… [baby’s] experience of close human contact with the provider of food…The sweetness of milk means goodness and pleasure not simply because of the taste, but because of the pleasurable associations with it”. She then goes onto say that the reasons for why sugar became a dominant part of the English diet cannot be traced back to “…the notion that ‘humans like the taste of sweetness’…”since there is variation of taste within culture, between cultures and through time (

Lupton 1996: 15). Although Lupton is correct in that taste cannot be solely due to genetics, it is a nurture-over-nature debate, a now dated argument as both genes and environment play important roles. However, we cannot

discount the crucial part genes play in taste. We are “programmed” to accept foods that are sweet, and to accept the familiar and not novel edibles (

Birch 1999: 45). While all newborns were found to prefer sweet over other, by 6 months of age, only infants that had been fed sweetened water by their mothers routinely, had a greater preference for it. “Preschool children repeatedly given tofu, either plain, salted, or sweetened, came to prefer the version they had become familiar with. This finding suggests that, in general, sweet taste is preferred but only in familiar food contexts” (

Ibid: 46). So, although the preference for sweet is innate, as we grow older, we become accustomed to the familiar, which is why we can acquire a preference for bitter taste, even though it is instinctive to dislike the taste. This then explains why tolerance of sugar varies cross-culturally e.g. Iranian sweet foods such as Baklava is usually considered sickly sweet to the British, while the same is said for the Christmas pudding (without icing) for the Iranian palate, although Iranians born in England gain partiality to English cakes and pastries (

Harbottle 1997: 182).

The genetic predisposition for sweetness may therefore explain overconsumption and addiction to sugar. McKenna (

1992: 175) argues that “Sugar abuse is the world’s least discussed and most widespread addiction…[it being] one of the hardest of all habits to kick…The depth of serious sugar addiction are exemplified by bulimics who may binge on sugar-saturated food…” and then vomit or take laxatives so that they can indulge in more sugar. McKenna correlates high sugar consumption with high alcohol consumption, saying that; “After alcohol and tobacco, sugar is the most damaging addictive substance consumed by human beings”. In the USA, obesity is increasing with approximately half of American adults classified as overweight (

Birch 1999: 42), this is said to be caused from American diets too high in total energy, sugar, fat, and too low in complex carbohydrates (

Ibid: 43). “The high and increasing prevalence of overweight individuals suggest that the predispositions that were

adaptive under conditions where food was scarce are not adaptive in today’s environment…where inexpensive foods high in sugar, fat, total energy, and salt are readily available (

Ibid: 45)”. However, overconsumption cannot be purely based on genetics, as Lupton said, since other forces must be at work to induce such extremes in certain countries. As noted by Mintz (

1985: 189); “…the average French person consumes less sucrose…” than the average English person. Like how many people were enslaved for the sugar trade, the consumption of sugar may be a form of covert slavery imposed upon the unaware citizen.

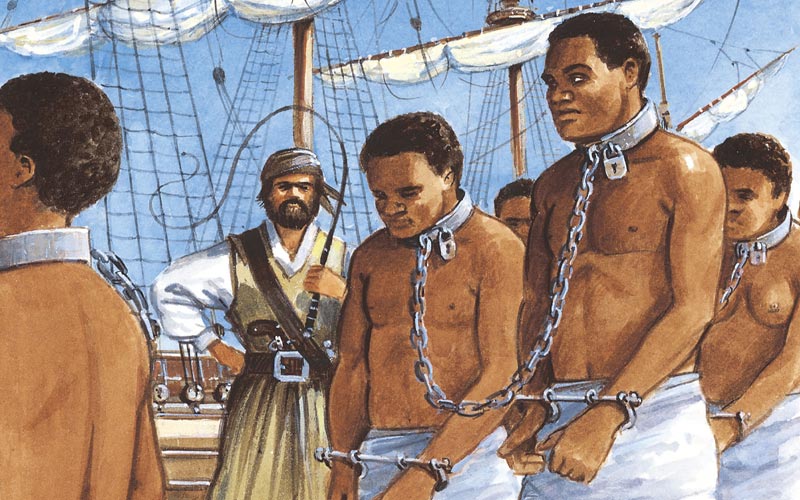

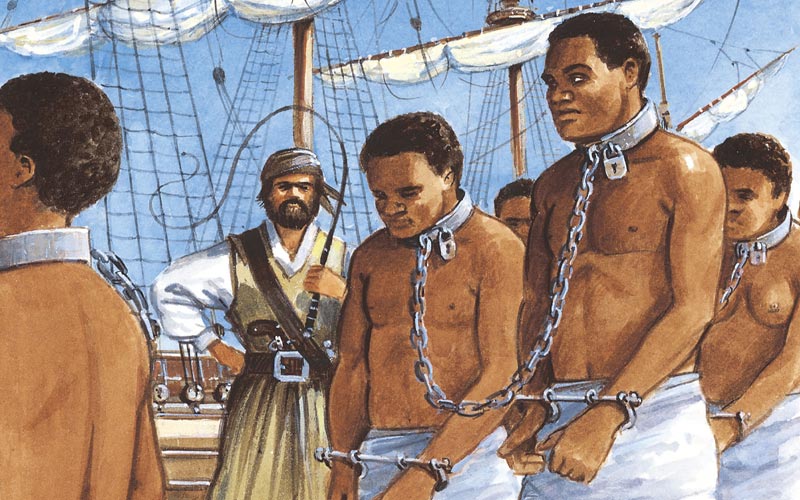

Sugar has has had a dark past. McKenna (

1992: 176) maintains that the

modern drug trade resembles nothing of the scale in which kidnapping,

transporting, and the mass murder of large populations happened in

fuelling the sugar trade. In the beginning of the sugar industry; the

Portuguese had Portuguese work on the sugar estates; usually convicts,

debtors and Jews who refused to convert to Christianity (

Hobhouse 2002: 63-64).

The Modern Sugar Slave Trade began, however, when Prince Henry of

Portugal's ships captured and enslaved a crew of Moslems, they were

released after arguing that the best slaves were to be found in the

hinterland of Africa. Thus trade began between Africa and southern

Europe. The Portuguese saw the Africans as less than human, for they

were children of Ham, and were not allowed to read or write, or convert

to Christianity. Some were sold to Spain (

Ibid: 66). Yet, there were not enough slaves to be imported to the Caribbean, where some of the

Spanish were settling. By 1530, slaves were sent directly from Africa to the Caribbean (

Ibid: 69).

But it was Bartolomé de Las Casas who, upon seeing how the native

Caribbean Caribs and Arawaks were forcibly made to do jobs that they

couldn’t or wouldn’t do (many choosing to die than except slavery) (

Ibid: 70),

that he “…suggested the introduction of blacks.” They were thought to

be docile beings, who would work willingly in servitude. The

transatlantic slave trade began. Abuse was harsh and commonplace upon

the slaves, and resigning his bishopric, Las Casas conducted a

nationwide campaign in 1548, against the trade he had started. His

efforts failed. It would be 200 years later before the slave trade would

once again be questioned (

Ibid: 71). Instead, many human lives

meant only in the service to the sugar trade; in 1645 Barbados, there

were 4000 black people (all slaves), and 18,000 white people (only 7000

were free) (

Ibid: 74). It is believed that 11.7 million slaves

were exported and “…9.8 million slaves imported into the New World

between 1450 and 1900” (

Ibid: 76), with one ton of sugar

representing “…the lifetime sugar production of one slave who had been

captured, manacled, marched to the African coast, penned like a pig to

await a buyer, sold, chained again on board ship, sold on the island

market…” and then seasoned to the Caribbean before they would show

profit to an owner. The slave’s whole life was equal to that of one ton

of refined sugar (

Ibid: 77). As Hobhouse (

2002: 79)

writes; “It was the first time since the Roman latifundia that mass

slavery had been used to grow a crop for trade (not subsistence)…It was

also the first time in history that one race had been uniquely selected

for a servile role.”

At the same time, the sugar industry chained the free person. Cultures everywhere that have remained in a habitat for a long time build up knowledge of the environment around them, as well as a sustainable diet. Industrial food can help to supplement diets, yet, transnational advertising, ethnocentrism and uninformed individuals leads to the devaluation of traditional cooking and increased consumption of junk foods [Which contains and is based on, high fats and sugars] (

Pilcher 2002: 223). Two examples of this can be seen in Britain and Mexico.

In Britain, sweetened tea and treacle were advertised in 1750, with mass consumption of sucrose happening around 1850 (

Mintz 1985: 147-148), making it available to the poor. Britons began to produce less of their own food, spending more time away from the home and eating elsewhere, healthy foods such as broths and porridges were replaced with high-energy jam and white bread. Now women were not spending time on preparing food, they too could join the work force (

Mintz 1997: 100). “Industrialisation drew people from the countryside, from their gardens and fields, woods and streams which had provided their food, to the tenements and back-to-back houses where they had to buy what they ate.” Buying cheap, store-bought, factory processed food allowed the abandonment of traditional cooking to spend more time working. Sugar was used as preservative, flavourer (

Galloway 1989: 7), and quick energy to the working class. “By positively affecting the worker’s energy output and productivity…[sugar] figured importantly in balancing the accounts of capitalism… (

Mintz 1985: 148)”. World sugar production rose from 572,000 tons in 1830 to 6,000,000 tons in 1890 [a 500% increase in 30 years] (

Ibid: 73).

In 20th century Mexico, road networks allowed bottled soft drinks to become a staple commodity, with servings accounting for 15% of Coke’s and 20% of Pepsi’s international sales in the 1990s. Pepsi’s label found on many junk foods has led to the company’s success over coke (

Leatherman & Goodman 2005: 839) with food manufacturers allowance to run mass advertising campaigns for soft

drinks and sweets, with only small print on advice to eat fresh fruit (

Pilcher 2002: 233-234), it is therefore not uncommon to see a young infant with a soft drink (

Leatherman & Goodman 2005: 839). Like that of sugary white bread replacing homemade loaves in Britain, fewer corn tortillas are eaten in Mexico, replaced instead with white flour tortillas [These are of course higher in sugar than the traditional corn tortillas] (

Ibid: 840).

Unlike metal or cloth, drug foods such as sugar, encourages immediate consumption through our innate disposition to like sweet substances. Sugar therefore, is less likely to be stored, causing consumer demand to either remain constant or increase (

Jankowiak & Bradburd 1996: 718). Through mass media and small print [e.g. Asda’s sticky chilli chicken and Tesco’s crispy beef was found to have more sugar content than vanilla ice cream (

BBC 2007)], consumers are removed from their nourishment, and to see packaged foods as more natural than living plants and animals (

Pilcher 2002: 236). As the body habitually gets sugar requirements from sucrose in processed foods, other enzymes are inhibited, making it difficult to digest starch and fibre. Naturally, people avoid what they cannot eat, and the manufacturers reduce fibre content and increase sugar content of factory foods. People become addicted, and disorders such as bulimia occur, overconsumption increases, and problems such as obesity, tooth problems and malnutrition are caused (

Hobhouse 2002: 58). In Mexico; diabetes is the fourth leading cause of death nationwide, with adults usually both obese and anaemic at the same time (

Pilcher 2002: 236).

To conclude, sugar has been used for centuries; written about in the Mahābhāshya [400 B.C] (Mintz 1985: 19), the Buddhagosa (Ibid: 23), and ancient Latin and Greek literature (Lupton 1996: 35). It was medicinal and used in many countries (Mintz 1985: 96-99). Sugar’s sweet taste is pleasurable to all humans, a genetic predisposition that tells us of its high energy content. Sugar didn’t always have a bad reputation. It wasn’t until mass quantities could be refined that its dark history was created, being used to push millions of people into slavery, whether overtly [working on the plantations] or covertly [“drug foods often serve as an alternative to military force and are generally selected because they are more efficient, more economical, or easier to sustain (Jankowiak & Bradburd1996:718)”]. Through today’s industry, we are taken away from being able to create food, manipulated into believing packaged is natural, swamped with a sugar overload from manufactured products. We overconsume, addicted to a taste that once was adaptive.

Bibliography

Armelagos, G. (1987). “Biocultural Aspects of Food choice” in Harris, M.

& Ross, E. B. (eds.). Food and

Evolution: Toward a theory of Human Food Habits. Temple University Press:

Philadelphia

Birch, L. L. (1999). “Development of Food Preferences”. Annual Review of Nutrition 19: 41-62.

Charles, J. (2002). “Searching for Gold in Guacamole: California Growers

Market the Avocado, 1910-1994” in Belasco, W. & Scranton, P. (eds.). Food Nations: Selling taste in Consumer

Societies. Routledge: New York

Dalby, A. (2000). Dangerous

Tastes: The Story of Spices. The British Museum Press: London

De Snoo, K. (1937). “Sucking Behaviour in the Human Fetus”. Monatsschrift Geburtshilfe 105: 88-97.

Galloway, J. H. (1989).

The Sugar Cane Industry: An historical geography from its Origins to

1914. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge

Harbottle, L. (1997). “Taste and Embodiment: The

Food preferences of Iranians in Britain” in Macbeth, H. (eds.).

Food Preferences and Taste: Continuity and

Change. Berghahn Books: Providence

Harris, M. (1987). “Foodways: Historical

Overview and Theoretical Prolegomenon” in Harris, M. & Ross, E. B. (eds.).

Food and Evolution: Toward a theory of Human

Food Habits. Temple University Press: Philadelphia

Hladik, C. M. (1997). “Primate Models for Taste

and Food Preferences” in Macbeth, H. (eds.).

Food Preferences and Taste: Continuity and Change. Berghahn Books:

Providence

Hobhouse, H. (2002).

Seeds of Change: Six plants that transformed mankind (Second

Edition). Pan Books: London

Jankowiak, W. & Bradburd, D. (1996). “Using

Drug Foods to Capture and Enhance Labour Performance: A Cross-Cultural

Perspective”.

Current Anthropology 37:

717-720.

Leatherman, T. & Goodman, A. (2005).

“Coca-colonisation of Diets in the Yucatan”.

Social Science and Medicine 61: 833-846.

Lupton, D. (1996).

Food, the Body and the Self. Sage Publications: London

McKenna, T. (1992).

Food of the Gods: The Search for the Original Tree of Knowledge - A Radical History of Plants, Drugs and

Human Evolution. Rider: London

Mintz, S. W. (1985).

Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History. Penguin

Books: New York

Mintz, S. W. (2008). “Time, Sugar, and

Sweetness” in Counihan, C. & Van Esterik, P. (eds.).

Food and Culture: A Reader (Second Edition). Routledge: New York

Pilcher. J. M. (2002). “Industrial Tortillas and

Folkloric Pepsi: The Nutritional Consequences of Hybrid Cuisines in Mexico” in

Belasco, W. & Scranton, P. (eds.).

Food

Nations: Selling taste in Consumer Societies. Routledge: New York

Simmen, B. (1997). “Food Preferences in

Neotropical Primates in Relation to Taste Sensitivity” in Macbeth, H. (eds.).

Food Preferences and Taste: Continuity and

Change. Berghahn Books: Providence

Online Sources

BBC. (2007). Savoury Foods High Sugar Warning